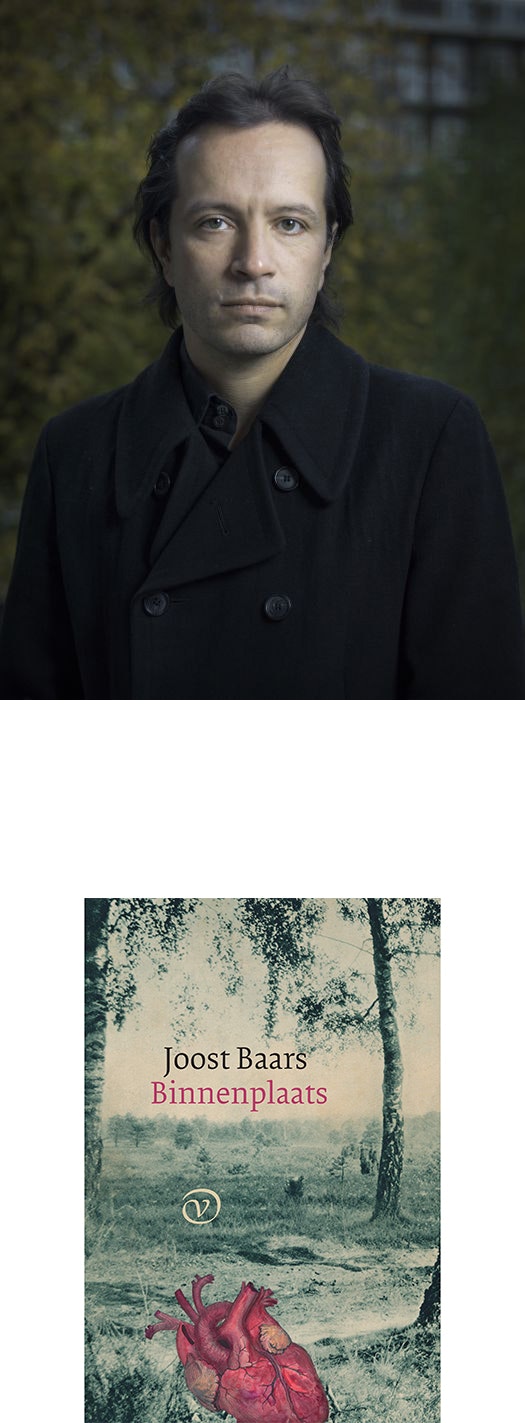

Shopper Stories: Joost Baars

Family Painting Rediscovered

Meet Joost Baars: Renowned Dutch poet, VSB Poetry Prize winner, and keeper of his grandfather’s legacy in the form of an authentic gallery wall. Joost’s EBTH discovery in March of 2019, helped him develop the ability to see through the eyes of a man he never met: a man with incredible artistic talent and an overwhelmingly emotional influence on Joost, his grandfather.

Joost begins -

I loved this find for a couple of reasons. First, it was the first one I found in North America. My grandfather traveled to Canada at one point in his life with the objective to be a painter. This is a peculiar decision, as most painters of his time would have gone to Berlin, Paris or the south of France to do that. But, aside from the fact that he had family there, I think he was drawn to the kind of landscapes he could find there: majestic landscapes in which you can be really alone. Anyhow, he took a couple of paintings with him, and later – after he was forced back to The Netherlands when his money ran out – sent some more to the family there. The painting probably crossed the Atlantic in either of those ways. I’m pretty sure he didn’t paint it over there – I would kill for a painting he did in Canada – because he always painted from sight and he did travel to the south of Europe sometimes to paint. And to me the painting looks like a fishing village in the south of Europe.

I really wanted the painting, so I was very happy when I won it. But it also filled me with some trepidation, because I had no clue what the shipping costs were going to be and if I would be able to pay them. Luckily, they were not nearly as bad as I feared.

I haven’t actually shared this one with my family yet. At least not in the flesh. I did send some photographs of course. They love it. They also love the fact that I’m searching for these paintings. My grandfather has left a void in the lives of my mother and her siblings. Telling his story is a way of keeping him alive, so I think it’s moving to them that the next generation is catching on to these stories.

It is particularly moving to share the paintings I acquire with my mother. She was only five when my grandfather, her father, died, so he did not only leave a void in her life, but also a void within the void, because she has always missed him without having a lot of first hand knowledge about whom she is missing. It’s as if her father did not only leave a void in her life, but also a void within that void. I took her with me to pick up the first painting I bought, and I will never forget the look in her eyes when I told the seller that she was in fact Harry Winter’s daughter. It was as if there was suddenly a connection there that wasn’t there before. It was as if the acknowledgement of the void in her life, and the void within the void, suddenly brought him back to life, made him more real than he ever was for her.

Neither I, nor my family, knew of the existence of this particular painting before I came across it on EBTH. My grandfather painted a lot, and also sold a lot, although he rarely could make a living from his painting alone. So there was a constant stream of paintings and a lot of them did not stay in the house. I am not in touch with my distant Canadian family, but they might recognise it.

For me, my connection to my grandfather’s work, is through my own work as a poet. Although I come from a family that appreciated art, I have always had the feeling that my desire to actually make it, and make it in a way that was more than just a hobby, came from nowhere. This has always made me very unsure of myself, and instilled in me the desire to be perceived as a real poet. This made me struggle for more than a decade, being unable to write good poetry let alone get it published. Eventually, I completely dried up, and it was at that point that I decided to give up my desire to be a real poet, or to be perceived as one, and explicitly resolved to only write what I would write if nobody would ever read it. This, ironically, made me capable of writing good poetry and led to my debut collection Binnenplaats (which translates roughly as ‘Enclosure’), which came out when I was 41. There’s more irony: this book that I explicitly wrote for nobody, having given up on the desire to be acknowledged, brought me more acknowledgement than I ever could hope for: it sold really well, was nominated for three prizes and won the most important prize for a single collection in the Dutch speaking world: the VSB Poetry Prize. Now, I’m struggling to regain my amateurism.

After I won the prize, I visited my mother, and my aunt was also there. She had made an album of photographs that tracked the family from the late 1800s up to the present day. I flipped through it, and came upon a lot of Harry Winter’s paintings. I recognised something in them. Harry was mostly a landscape and cityscape painter, and painted landscapes mostly without any people in them. He wasn’t concerned with being modern, and at the same time he wasn’t particularly nostalgic either, at least not in his best work. His paintings did not scream for attention in any way, but seemed to me to be quiet reflections on the landscapes or cityscapes in which he painted them. Binnenplaats partly consists of poems doing exactly the same thing: not trying to be ‘of these times’, not trying to be remarkable, but quietly reflecting on a landscape, in my case the giant garden that lays under the balcony of my Amsterdam apartment. I wrote prayers – I literally talked to that garden, as if no one else was there – and seeing Harry’s paintings I felt that he was doing the same thing.

Maybe I wanted to feel that. Of course I don’t have any clue about the true motivations of my grandfather as an artist. But a few pages on in the photo album, I suddenly saw myself. My aunt had included pictures of the award ceremony, and had captioned them by deeming me the official successor of Harry Winter. This was incredibly moving. I suddenly knew exactly where my desire to make art came from. And the fact that I thought I recognised a certain way of looking in Harry’s paintings, only reinforced this idea. This made me want to acquire Harry’s paintings, to surround myself with them, because I wanted to learn to look through his eyes, and by that to gain a better understanding about the way I was looking. And maybe also to regain my amateurism.

Clarice Lispector once said in an interview: ‘I’m an amateur and insist on staying that way. A professional has a personal commitment to writing. Or a commitment to someone else to write. As for me… I insist on not being a professional. To keep my freedom.’ I know that Harry Winter wasn’t the best painter of his generation, or even the best painter he could have been. There are things that he clearly wasn’t good at, like painting people. You can see on the painting I bought from EBTH that the people in the painting are actually way too small. Yet, you can also see that he is very good at painting skies and clouds, and also at composing scenery. And more importantly: there’s something there that I can’t quite put my finger on. It’s not that he is good at some particular technique, it’s just that these paintings have blood in them. This is not a hobbyist at work, someone who just paints for distraction. This is someone who must paint. And also, someone who paints with the utmost respect for what he is painting. I can see a sense of prayer, of devotion in his work, which was very opposite to the times in which he lived. Artists of his generation wanted to change the world. It seems to me that he wanted the world to change him.

I may be making all this up. I hardly know anything about him. But it is what I see in his paintings. And somehow, the way these paintings fill a void in my mother’s life, has something to do with the way they fill a void in mine. Whatever is true about what I think to see in his paintings, the things we see in them has made my mother and me talk more about her father and has brought us closer together. So I think something about it must be right.

In short, it seems to me a painting of a southern European fishing village. It has a lot of atmosphere, especially for its use of color and the way Harry paints skies, clouds and light. The colors and the light are interesting because they are very different from the colours and light in his Dutch paintings, which is simply due, I think, to the fact that lights and colours are very different here than in southern Europe. This tells me something about the meticulousness of his gaze, the measure in which he was open to be influenced by his surroundings. Something that I also see in his war years and post-war years. What is also apparent, is that when he paints people in his landscapes, the proportions tend to become confused. The people in this painting are too small. This flaw is present in more paintings that have people or other living creatures in them. This is of course just due to the fact that a painter can be good at one thing – light – but bad at another – people. But, being a poet, I can’t help but reading something more into this: a desire to be alone. Maybe the people that sold his paintings for him had told him that the inclusion of people in the paintings would make his paintings more cozy and therefore more salable. Maybe it’s not that he lacked a talent for painting people, but that his heart just wasn’t into it.

Another thing that’s unique about this painting, is something that his best paintings all have, and that might be my most favorite thing about them. It is that the paintings that play with light and colour extensively tend to move along with the natural light that shines on them. This means that when you look at the painting in morning light, it is morning on the painting. When you look in the afternoon, it is the afternoon. Even when you look at night, with the lights off, the painting is still there as a nightly scenery. This is the most remarkable quality of Harry’s work, and it is a quality that is invisible to anyone who would just look at the painting once or twice, for a moment. You really have to live with them to see it.

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

14K 0.04 CTW Diamond Mushroom Stud Earrings

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

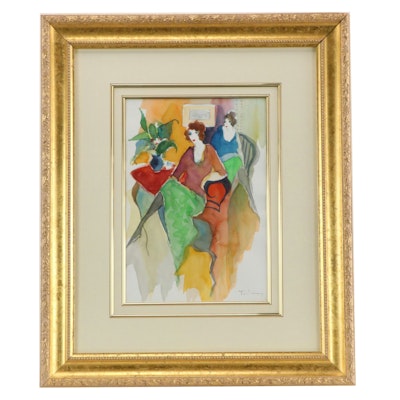

Itzchak Tarkay Hand-Colored Lithograph, 21st Century

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

14K Amethyst, Diamond and CZ Ring

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

10K Button Earrings

I don’t know a lot about my grandfather. He died when my mother (the youngest of her siblings) was only five years old. His story is roughly as follows. He had always been a painter. He started painting under the influence of the Hague School, an art movement that was hugely and internationally popular and successful in the 1910s and 1920s, but quickly lost its significance after that, when the avant-garde-movements came about. Yet, he kept at it, as so many artists of his time did. Probably also because while the art movement lost its significance, it did not lose its popularity for quite a while. But not solely because of that, because as I said, I can’t deny that what I see in his work is not pastiche, it is the real thing, whatever that may be. For all his un-modernity, there is something in his work that did survive the passing of time.

He was an autodidact. He did not go to any academy. But he did learn from peers and elders. I know he befriended Frans Hoos – I also own a small portrait of Harry painted by Hoos – a painter who was a few decades older than him. He went to Canada in either 1932 or 1933, to paint, or maybe ‘to make it as a painter’, as they say. He wrote letters to his girlfriend, and after he was forced back to The Netherlands for lack of money, he married her and started his family. To make a living, they started a trade business in sour herring. Later on, he employed his painting skills by making imitation Delfts Blauw tiles, which he sold. During the war there was a small period in which he could live from his painting alone, probably due to the questionable resurgence of interest in nostalgic, nationalist and figurative art during fascism.

During the war, he did some work for the resistance and the family also had at least one Jewish hideaway. She decided to relocate to Amsterdam after a while, where she eventually was rounded up and deported. A week before this happened, he saw her on a visit to Amsterdam, and invited her to come back. After the war, when collaborator-women were shaved, beaten, raped and imprisoned, he made a scene at a The Hague prison to get a German neighbour free. I have no idea if this neighbour had done anything during the war that made her deserve what she was going through – this period of reckoning in The Netherlands was wild and spontaneous and did not always have something to do with due process – but Harry succeeded in getting her out. My aunt says that he came back from the prison with a sore throat and having lost his voice. A few years later, he came down with cancer. He died in 1954.

As far as legacy goes, I do want to write about Harry. Whether it would be poetry or something else, I don’t know. Or even whether I will write anything significantly at all. That is not up to me. But I do love crawling behind his eyes by looking at a painting, and wondering what he was thinking while painting it.

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

14K Rutilated Quartz Ring

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Jasper, Sandstone, Abalone and Other Gemstone Globe with Brushed Copper Stand

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Mid Century Modern Chromed Metal and Acrylic Sputnik Pendant, 21st Century

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Hermès "Junques et Sampans" Silk Twill Scarf 90

I live in a very small apartment, so there is hardly any room for paintings. I own six [of Harry’s pieces] now. There is a tiny alcove in our living room, and we’ve hung them all there, calling it ‘The Winter Museum’. It’s great to just sit there and watch– to just be surrounded by these paintings. It gives me a sense of home that I never knew.

It’s certainly an item with a story, but, then again, I think there is probably nothing that EBTH sells that doesn’t have some kind of story attached to it. The painting is not particularly valuable, it’s not of any time, it’s not historically significant. It’s not even perfect. But that’s exactly why it is beautiful– why I love my grandfather’s art: because it doesn’t try to be any of those things. Because it was made within an already dying painting-style, by a painter that was talented but far from perfect, and – at least to me – somehow survived all these things and speaks to me directly today. That is kind of a miracle.

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Michal P. Sherman Oil Painting "Roman Streetscape"

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

14K 1.87 CTW Lab Grown Diamond Ring with IGI Online Report

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Webster Co. Sterling Silver Cigarette Case

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Loose 2.03 CT Ruby

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Philippe Halsman Photograph of Warhol's Factory (Posthumous Printing), 1989

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Hermès "Etriers" Silk Twill Scarf 90

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

MCM Abstract Carved Stone Bust

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

1998 Omega 18K and Stainless Steel Constellation Quartz Watch

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Howard Miller "Childress" Footed Metal Mantel Clock

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Aaron Wooten Acrylic Painting "Holly Jolly Trees," 2023

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash

Prince Promo Poster for ‘Art Official Age’ Album

EBTH Cincinnati - Blue Ash